THE MURDER OFROGER ACKROYD

CONTENTS

CHAPTER |

PAGE |

|

|---|---|---|

| DR. SHEPPARD AT THE BREAKFAST TABLE | 1 |

|

| WHO’S WHO IN KING’S ABBOT | 7 |

|

| THE MAN WHO GREW VEGETABLE MARROWS | 17 |

|

| DINNER AT FERNLY | 31 |

|

| MURDER | 49 |

|

| THE TUNISIAN DAGGER | 65 |

|

| I LEARN MY NEIGHBOR’S PROFESSION | 75 |

|

| INSPECTOR RAGLAN IS CONFIDENT | 92 |

|

| THE GOLDFISH POND | 106 |

|

| THE PARLORMAID | 118 |

|

| POIROT PAYS A CALL | 136 |

|

| ROUND THE TABLE | 145 |

|

| THE GOOSE QUILL | 156 |

|

| MRS. ACKROYD | 165 |

|

| GEOFFREY RAYMOND | 178 |

|

| AN EVENING AT MAH JONG | 190 |

|

| PARKER | 202 |

|

| CHARLES KENT | 218 |

|

| FLORA ACKROYD | 226 |

|

| MISS RUSSELL | 238 |

|

| THE PARAGRAPH IN THE PAPER | 251 |

|

| URSULA’S STORY | 260 |

|

| POIROT’S LITTLE REUNION | 269 |

|

| RALPH PATON’S STORY | 284 |

|

| THE WHOLE TRUTH | 289 |

|

| AND NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH | 298 |

|

| APOLOGIA | 303 |

ROGER ACKROYD

CHAPTER I

Mrs. Ferrars died on the night of the 16th–17th September—a Thursday. I was sent for at eight o’clock on the morning of Friday the 17th. There was nothing to be done. She had been dead some hours.

It was just a few minutes after nine when I reached home once more. I opened the front door with my latch-key, and purposely delayed a few moments in the hall, hanging up my hat and the light overcoat that I had deemed a wise precaution against the chill of an early autumn morning. To tell the truth, I was considerably upset and worried. I am not going to pretend that at that moment I foresaw the events of the next few weeks. I emphatically did not do so. But my instinct told me that there were stirring times ahead.

From the dining-room on my left there came the rattle of tea-cups and the short, dry cough of my sister Caroline.

“Is that you, James?” she called.

An unnecessary question, since who else could it be? To tell the truth, it was precisely my sister Caroline who was the cause of my few minutes’ delay. The motto of the mongoose family, so Mr. Kipling tells us, is: “Go and find out.” If Caroline ever adopts a crest, I should certainly suggest a mongoose rampant. One2 might omit the first part of the motto. Caroline can do any amount of finding out by sitting placidly at home. I don’t know how she manages it, but there it is. I suspect that the servants and the tradesmen constitute her Intelligence Corps. When she goes out, it is not to gather in information, but to spread it. At that, too, she is amazingly expert.

It was really this last named trait of hers which was causing me these pangs of indecision. Whatever I told Caroline now concerning the demise of Mrs. Ferrars would be common knowledge all over the village within the space of an hour and a half. As a professional man, I naturally aim at discretion. Therefore I have got into the habit of continually withholding all information possible from my sister. She usually finds out just the same, but I have the moral satisfaction of knowing that I am in no way to blame.

Mrs. Ferrars’ husband died just over a year ago, and Caroline has constantly asserted, without the least foundation for the assertion, that his wife poisoned him.

She scorns my invariable rejoinder that Mr. Ferrars died of acute gastritis, helped on by habitual over-indulgence in alcoholic beverages. The symptoms of gastritis and arsenical poisoning are not, I agree, unlike, but Caroline bases her accusation on quite different lines.

“You’ve only got to look at her,” I have heard her say.

Mrs. Ferrars, though not in her first youth, was a very attractive woman, and her clothes, though simple, always seemed to fit her very well, but all the same, lots of women buy their clothes in Paris and have not, on that account, necessarily poisoned their husbands.

3

As I stood hesitating in the hall, with all this passing through my mind, Caroline’s voice came again, with a sharper note in it.

“What on earth are you doing out there, James? Why don’t you come and get your breakfast?”

“Just coming, my dear,” I said hastily. “I’ve been hanging up my overcoat.”

“You could have hung up half a dozen overcoats in this time.”

She was quite right. I could have.

I walked into the dining-room, gave Caroline the accustomed peck on the cheek, and sat down to eggs and bacon. The bacon was rather cold.

“You’ve had an early call,” remarked Caroline.

“Yes,” I said. “King’s Paddock. Mrs. Ferrars.”

“I know,” said my sister.

“How did you know?”

“Annie told me.”

Annie is the house parlormaid. A nice girl, but an inveterate talker.

There was a pause. I continued to eat eggs and bacon. My sister’s nose, which is long and thin, quivered a little at the tip, as it always does when she is interested or excited over anything.

“Well?” she demanded.

“A bad business. Nothing to be done. Must have died in her sleep.”

“I know,” said my sister again.

This time I was annoyed.

“You can’t know,” I snapped. “I didn’t know myself4 until I got there, and I haven’t mentioned it to a soul yet. If that girl Annie knows, she must be a clairvoyant.”

“It wasn’t Annie who told me. It was the milkman. He had it from the Ferrars’ cook.”

As I say, there is no need for Caroline to go out to get information. She sits at home, and it comes to her.

My sister continued:

“What did she die of? Heart failure?”

“Didn’t the milkman tell you that?” I inquired sarcastically.

Sarcasm is wasted on Caroline. She takes it seriously and answers accordingly.

“He didn’t know,” she explained.

After all, Caroline was bound to hear sooner or later. She might as well hear from me.

“She died of an overdose of veronal. She’s been taking it lately for sleeplessness. Must have taken too much.”

“Nonsense,” said Caroline immediately. “She took it on purpose. Don’t tell me!”

It is odd how, when you have a secret belief of your own which you do not wish to acknowledge, the voicing of it by some one else will rouse you to a fury of denial. I burst immediately into indignant speech.

“There you go again,” I said. “Rushing along without rhyme or reason. Why on earth should Mrs. Ferrars wish to commit suicide? A widow, fairly young still, very well off, good health, and nothing to do but enjoy life. It’s absurd.”

5

“Not at all. Even you must have noticed how different she has been looking lately. It’s been coming on for the last six months. She’s looked positively hag-ridden. And you have just admitted that she hasn’t been able to sleep.”

“What is your diagnosis?” I demanded coldly. “An unfortunate love affair, I suppose?”

My sister shook her head.

“Remorse,” she said, with great gusto.

“Remorse?”

“Yes. You never would believe me when I told you she poisoned her husband. I’m more than ever convinced of it now.”

“I don’t think you’re very logical,” I objected. “Surely if a woman committed a crime like murder, she’d be sufficiently cold-blooded to enjoy the fruits of it without any weak-minded sentimentality such as repentance.”

Caroline shook her head.

“There probably are women like that—but Mrs. Ferrars wasn’t one of them. She was a mass of nerves. An overmastering impulse drove her on to get rid of her husband because she was the sort of person who simply can’t endure suffering of any kind, and there’s no doubt that the wife of a man like Ashley Ferrars must have had to suffer a good deal——”

I nodded.

“And ever since she’s been haunted by what she did. I can’t help feeling sorry for her.”

I don’t think Caroline ever felt sorry for Mrs. Ferrars whilst she was alive. Now that she has gone where (presumably)6 Paris frocks can no longer be worn, Caroline is prepared to indulge in the softer emotions of pity and comprehension.

I told her firmly that her whole idea was nonsense. I was all the more firm because I secretly agreed with some part, at least, of what she had said. But it is all wrong that Caroline should arrive at the truth simply by a kind of inspired guesswork. I wasn’t going to encourage that sort of thing. She will go round the village airing her views, and every one will think that she is doing so on medical data supplied by me. Life is very trying.

“Nonsense,” said Caroline, in reply to my strictures. “You’ll see. Ten to one she’s left a letter confessing everything.”

“She didn’t leave a letter of any kind,” I said sharply, and not seeing where the admission was going to land me.

“Oh!” said Caroline. “So you did inquire about that, did you? I believe, James, that in your heart of hearts, you think very much as I do. You’re a precious old humbug.”

“One always has to take the possibility of suicide into consideration,” I said repressively.

“Will there be an inquest?”

“There may be. It all depends. If I am able to declare myself absolutely satisfied that the overdose was taken accidentally, an inquest might be dispensed with.”

“And are you absolutely satisfied?” asked my sister shrewdly.

I did not answer, but got up from table.

CHAPTER II

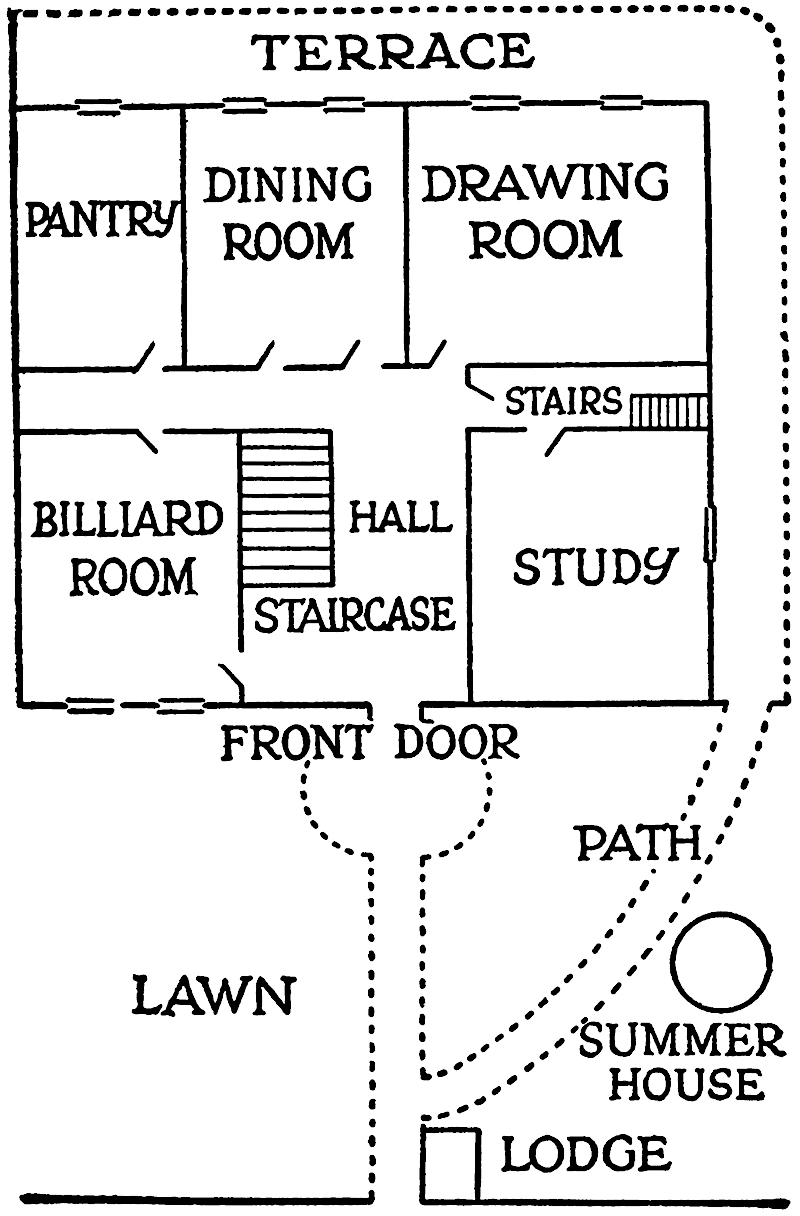

Before I proceed further with what I said to Caroline and what Caroline said to me, it might be as well to give some idea of what I should describe as our local geography. Our village, King’s Abbot, is, I imagine, very much like any other village. Our big town is Cranchester, nine miles away. We have a large railway station, a small post office, and two rival “General Stores.” Able-bodied men are apt to leave the place early in life, but we are rich in unmarried ladies and retired military officers. Our hobbies and recreations can be summed up in the one word, “gossip.”

There are only two houses of any importance in King’s Abbot. One is King’s Paddock, left to Mrs. Ferrars by her late husband. The other, Fernly Park, is owned by Roger Ackroyd. Ackroyd has always interested me by being a man more impossibly like a country squire than any country squire could really be. He reminds one of the red-faced sportsmen who always appeared early in the first act of an old-fashioned musical comedy, the setting being the village green. They usually sang a song about going up to London. Nowadays we have revues, and the country squire has died out of musical fashion.

Of course, Ackroyd is not really a country squire. He8 is an immensely successful manufacturer of (I think) wagon wheels. He is a man of nearly fifty years of age, rubicund of face and genial of manner. He is hand and glove with the vicar, subscribes liberally to parish funds (though rumor has it that he is extremely mean in personal expenditure), encourages cricket matches, Lads’ Clubs, and Disabled Soldiers’ Institutes. He is, in fact, the life and soul of our peaceful village of King’s Abbot.

Now when Roger Ackroyd was a lad of twenty-one, he fell in love with, and married, a beautiful woman some five or six years his senior. Her name was Paton, and she was a widow with one child. The history of the marriage was short and painful. To put it bluntly, Mrs. Ackroyd was a dipsomaniac. She succeeded in drinking herself into her grave four years after her marriage.

In the years that followed, Ackroyd showed no disposition to make a second matrimonial adventure. His wife’s child by her first marriage was only seven years old when his mother died. He is now twenty-five. Ackroyd has always regarded him as his own son, and has brought him up accordingly, but he has been a wild lad and a continual source of worry and trouble to his stepfather. Nevertheless we are all very fond of Ralph Paton in King’s Abbot. He is such a good-looking youngster for one thing.

As I said before, we are ready enough to gossip in our village. Everybody noticed from the first that Ackroyd and Mrs. Ferrars got on very well together. After her husband’s death, the intimacy became more marked. They were always seen about together, and it was freely9 conjectured that at the end of her period of mourning, Mrs. Ferrars would become Mrs. Roger Ackroyd. It was felt, indeed, that there was a certain fitness in the thing. Roger Ackroyd’s wife had admittedly died of drink. Ashley Ferrars had been a drunkard for many years before his death. It was only fitting that these two victims of alcoholic excess should make up to each other for all that they had previously endured at the hands of their former spouses.

The Ferrars only came to live here just over a year ago, but a halo of gossip has surrounded Ackroyd for many years past. All the time that Ralph Paton was growing up to manhood, a series of lady housekeepers presided over Ackroyd’s establishment, and each in turn was regarded with lively suspicion by Caroline and her cronies. It is not too much to say that for at least fifteen years the whole village has confidently expected Ackroyd to marry one of his housekeepers. The last of them, a redoubtable lady called Miss Russell, has reigned undisputed for five years, twice as long as any of her predecessors. It is felt that but for the advent of Mrs. Ferrars, Ackroyd could hardly have escaped. That—and one other factor—the unexpected arrival of a widowed sister-in-law with her daughter from Canada. Mrs. Cecil Ackroyd, widow of Ackroyd’s ne’er-do-well younger brother, has taken up her residence at Fernly Park, and has succeeded, according to Caroline, in putting Miss Russell in her proper place.

I don’t know exactly what a “proper place” constitutes—it sounds chilly and unpleasant—but I know that10 Miss Russell goes about with pinched lips, and what I can only describe as an acid smile, and that she professes the utmost sympathy for “poor Mrs. Ackroyd—dependent on the charity of her husband’s brother. The bread of charity is so bitter, is it not? I should be quite miserable if I did not work for my living.”

I don’t know what Mrs. Cecil Ackroyd thought of the Ferrars affair when it came on the tapis. It was clearly to her advantage that Ackroyd should remain unmarried. She was always very charming—not to say gushing—to Mrs. Ferrars when they met. Caroline says that proves less than nothing.

Such have been our preoccupations in King’s Abbot for the last few years. We have discussed Ackroyd and his affairs from every standpoint. Mrs. Ferrars has fitted into her place in the scheme.

Now there has been a rearrangement of the kaleidoscope. From a mild discussion of probable wedding presents, we have been jerked into the midst of tragedy.

Revolving these and sundry other matters in my mind, I went mechanically on my round. I had no cases of special interest to attend, which was, perhaps, as well, for my thoughts returned again and again to the mystery of Mrs. Ferrars’s death. Had she taken her own life? Surely, if she had done so, she would have left some word behind to say what she contemplated doing? Women, in my experience, if they once reach the determination to commit suicide, usually wish to reveal the state of mind that led to the fatal action. They covet the limelight.

11

When had I last seen her? Not for over a week. Her manner then had been normal enough considering—well—considering everything.

Then I suddenly remembered that I had seen her, though not to speak to, only yesterday. She had been walking with Ralph Paton, and I had been surprised because I had had no idea that he was likely to be in King’s Abbot. I thought, indeed, that he had quarreled finally with his stepfather. Nothing had been seen of him down here for nearly six months. They had been walking along, side by side, their heads close together, and she had been talking very earnestly.

I think I can safely say that it was at this moment that a foreboding of the future first swept over me. Nothing tangible as yet—but a vague premonition of the way things were setting. That earnest tête-à-tête between Ralph Paton and Mrs. Ferrars the day before struck me disagreeably.

I was still thinking of it when I came face to face with Roger Ackroyd.

“Sheppard!” he exclaimed. “Just the man I wanted to get hold of. This is a terrible business.”

“You’ve heard then?”

He nodded. He had felt the blow keenly, I could see. His big red cheeks seemed to have fallen in, and he looked a positive wreck of his usual jolly, healthy self.

“It’s worse than you know,” he said quietly. “Look here, Sheppard, I’ve got to talk to you. Can you come back with me now?”

12

“Hardly. I’ve got three patients to see still, and I must be back by twelve to see my surgery patients.”

“Then this afternoon—no, better still, dine to-night. At 7.30? Will that suit you?”

“Yes—I can manage that all right. What’s wrong? Is it Ralph?”

I hardly knew why I said that—except, perhaps, that it had so often been Ralph.

Ackroyd stared blankly at me as though he hardly understood. I began to realize that there must be something very wrong indeed somewhere. I had never seen Ackroyd so upset before.

“Ralph?” he said vaguely. “Oh! no, it’s not Ralph. Ralph’s in London——Damn! Here’s old Miss Ganett coming. I don’t want to have to talk to her about this ghastly business. See you to-night, Sheppard. Seven-thirty.”

I nodded, and he hurried away, leaving me wondering. Ralph in London? But he had certainly been in King’s Abbot the preceding afternoon. He must have gone back to town last night or early this morning, and yet Ackroyd’s manner had conveyed quite a different impression. He had spoken as though Ralph had not been near the place for months.

I had no time to puzzle the matter out further. Miss Ganett was upon me, thirsting for information. Miss Ganett has all the characteristics of my sister Caroline, but she lacks that unerring aim in jumping to conclusions which lends a touch of greatness to Caroline’s13 maneuvers. Miss Ganett was breathless and interrogatory.

Wasn’t it sad about poor dear Mrs. Ferrars? A lot of people were saying she had been a confirmed drug-taker for years. So wicked the way people went about saying things. And yet, the worst of it was, there was usually a grain of truth somewhere in these wild statements. No smoke without fire! They were saying too that Mr. Ackroyd had found out about it, and had broken off the engagement—because there was an engagement. She, Miss Ganett, had proof positive of that. Of course I must know all about it—doctors always did—but they never tell?

And all this with a sharp beady eye on me to see how I reacted to these suggestions. Fortunately long association with Caroline has led me to preserve an impassive countenance, and to be ready with small non-committal remarks.

On this occasion I congratulated Miss Ganett on not joining in ill-natured gossip. Rather a neat counterattack, I thought. It left her in difficulties, and before she could pull herself together, I had passed on.

I went home thoughtful, to find several patients waiting for me in the surgery.

I had dismissed the last of them, as I thought, and was just contemplating a few minutes in the garden before lunch when I perceived one more patient waiting for me. She rose and came towards me as I stood somewhat surprised.

I don’t know why I should have been, except that there14 is a suggestion of cast iron about Miss Russell, a something that is above the ills of the flesh.

Ackroyd’s housekeeper is a tall woman, handsome but forbidding in appearance. She has a stern eye, and lips that shut tightly, and I feel that if I were an under housemaid or a kitchenmaid I should run for my life whenever I heard her coming.

“Good morning, Dr. Sheppard,” said Miss Russell. “I should be much obliged if you would take a look at my knee.”

I took a look, but, truth to tell, I was very little wiser when I had done so. Miss Russell’s account of vague pains was so unconvincing that with a woman of less integrity of character I should have suspected a trumped-up tale. It did cross my mind for one moment that Miss Russell might have deliberately invented this affection of the knee in order to pump me on the subject of Mrs. Ferrars’s death, but I soon saw that there, at least, I had misjudged her. She made a brief reference to the tragedy, nothing more. Yet she certainly seemed disposed to linger and chat.

“Well, thank you very much for this bottle of liniment, doctor,” she said at last. “Not that I believe it will do the least good.”

I didn’t think it would either, but I protested in duty bound. After all, it couldn’t do any harm, and one must stick up for the tools of one’s trade.

“I don’t believe in all these drugs,” said Miss Russell, her eyes sweeping over my array of bottles disparagingly.15 “Drugs do a lot of harm. Look at the cocaine habit.”

“Well, as far as that goes——”

“It’s very prevalent in high society.”

I’m sure Miss Russell knows far more about high society than I do. I didn’t attempt to argue with her.

“Just tell me this, doctor,” said Miss Russell. “Suppose you are really a slave of the drug habit. Is there any cure?”

One cannot answer a question like that offhand. I gave her a short lecture on the subject, and she listened with close attention. I still suspected her of seeking information about Mrs. Ferrars.

“Now, veronal, for instance——” I proceeded.

But, strangely enough, she didn’t seem interested in veronal. Instead she changed the subject, and asked me if it was true that there were certain poisons so rare as to baffle detection.

“Ah!” I said. “You’ve been reading detective stories.”

She admitted that she had.

“The essence of a detective story,” I said, “is to have a rare poison—if possible something from South America, that nobody has ever heard of—something that one obscure tribe of savages use to poison their arrows with. Death is instantaneous, and Western science is powerless to detect it. That is the kind of thing you mean?”

“Yes. Is there really such a thing?”

I shook my head regretfully.

“I’m afraid there isn’t. There’s curare, of course.”

I told her a good deal about curare, but she seemed to16 have lost interest once more. She asked me if I had any in my poison cupboard, and when I replied in the negative I fancy I fell in her estimation.

She said she must be getting back, and I saw her out at the surgery door just as the luncheon gong went.

I should never have suspected Miss Russell of a fondness for detective stories. It pleases me very much to think of her stepping out of the housekeeper’s room to rebuke a delinquent housemaid, and then returning to a comfortable perusal of The Mystery of the Seventh Death, or something of the kind.

CHAPTER III

I told Caroline at lunch time that I should be dining at Fernly. She expressed no objection—on the contrary——

“Excellent,” she said. “You’ll hear all about it. By the way, what is the trouble with Ralph?”

“With Ralph?” I said, surprised; “there’s isn’t any.”

“Then why is he staying at the Three Boars instead of at Fernly Park?”

I did not for a minute question Caroline’s statement that Ralph Paton was staying at the local inn. That Caroline said so was enough for me.

“Ackroyd told me he was in London,” I said. In the surprise of the moment I departed from my valuable rule of never parting with information.

“Oh!” said Caroline. I could see her nose twitching as she worked on this.

“He arrived at the Three Boars yesterday morning,” she said. “And he’s still there. Last night he was out with a girl.”

That did not surprise me in the least. Ralph, I should say, is out with a girl most nights of his life. But I did rather wonder that he chose to indulge in the pastime in King’s Abbot instead of in the gay metropolis.

“One of the barmaids?” I asked.

18

“No. That’s just it. He went out to meet her. I don’t know who she is.”

(Bitter for Caroline to have to admit such a thing.)

“But I can guess,” continued my indefatigable sister.

I waited patiently.

“His cousin.”

“Flora Ackroyd?” I exclaimed in surprise.

Flora Ackroyd is, of course, no relation whatever really to Ralph Paton, but Ralph has been looked upon for so long as practically Ackroyd’s own son, that cousinship is taken for granted.

“Flora Ackroyd,” said my sister.

“But why not go to Fernly if he wanted to see her?”

“Secretly engaged,” said Caroline, with immense enjoyment. “Old Ackroyd won’t hear of it, and they have to meet this way.”

I saw a good many flaws in Caroline’s theory, but I forbore to point them out to her. An innocent remark about our new neighbor created a diversion.

The house next door, The Larches, has recently been taken by a stranger. To Caroline’s extreme annoyance, she has not been able to find out anything about him, except that he is a foreigner. The Intelligence Corps has proved a broken reed. Presumably the man has milk and vegetables and joints of meat and occasional whitings just like everybody else, but none of the people who make it their business to supply these things seem to have acquired any information. His name, apparently, is Mr. Porrott—a name which conveys an odd feeling of unreality. The one thing we do know about him is that19 he is interested in the growing of vegetable marrows.

But that is certainly not the sort of information that Caroline is after. She wants to know where he comes from, what he does, whether he is married, what his wife was, or is, like, whether he has children, what his mother’s maiden name was—and so on. Somebody very like Caroline must have invented the questions on passports, I think.

“My dear Caroline,” I said. “There’s no doubt at all about what the man’s profession has been. He’s a retired hairdresser. Look at that mustache of his.”

Caroline dissented. She said that if the man was a hairdresser, he would have wavy hair—not straight. All hairdressers did.

I cited several hairdressers personally known to me who had straight hair, but Caroline refused to be convinced.

“I can’t make him out at all,” she said in an aggrieved voice. “I borrowed some garden tools the other day, and he was most polite, but I couldn’t get anything out of him. I asked him point blank at last whether he was a Frenchman, and he said he wasn’t—and somehow I didn’t like to ask him any more.”

I began to be more interested in our mysterious neighbor. A man who is capable of shutting up Caroline and sending her, like the Queen of Sheba, empty away must be something of a personality.

“I believe,” said Caroline, “that he’s got one of those new vacuum cleaners——”

I saw a meditated loan and the opportunity of further20 questioning gleaming from her eye. I seized the chance to escape into the garden. I am rather fond of gardening. I was busily exterminating dandelion roots when a shout of warning sounded from close by and a heavy body whizzed by my ear and fell at my feet with a repellant squelch. It was a vegetable marrow!

I looked up angrily. Over the wall, to my left, there appeared a face. An egg-shaped head, partially covered with suspiciously black hair, two immense mustaches, and a pair of watchful eyes. It was our mysterious neighbor, Mr. Porrott.

He broke at once into fluent apologies.

“I demand of you a thousand pardons, monsieur. I am without defense. For some months now I cultivate the marrows. This morning suddenly I enrage myself with these marrows. I send them to promenade themselves—alas! not only mentally but physically. I seize the biggest. I hurl him over the wall. Monsieur, I am ashamed. I prostrate myself.”

Before such profuse apologies, my anger was forced to melt. After all, the wretched vegetable hadn’t hit me. But I sincerely hoped that throwing large vegetables over walls was not our new friend’s hobby. Such a habit could hardly endear him to us as a neighbor.

The strange little man seemed to read my thoughts.

“Ah! no,” he exclaimed. “Do not disquiet yourself. It is not with me a habit. But can you figure to yourself, monsieur, that a man may work towards a certain object, may labor and toil to attain a certain kind of leisure and occupation, and then find that, after all, he yearns for21 the old busy days, and the old occupations that he thought himself so glad to leave?”

“Yes,” I said slowly. “I fancy that that is a common enough occurrence. I myself am perhaps an instance. A year ago I came into a legacy—enough to enable me to realize a dream. I have always wanted to travel, to see the world. Well, that was a year ago, as I said, and—I am still here.”

My little neighbor nodded.

“The chains of habit. We work to attain an object, and the object gained, we find that what we miss is the daily toil. And mark you, monsieur, my work was interesting work. The most interesting work there is in the world.”

“Yes?” I said encouragingly. For the moment the spirit of Caroline was strong within me.

“The study of human nature, monsieur!”

“Just so,” I said kindly.

Clearly a retired hairdresser. Who knows the secrets of human nature better than a hairdresser?

“Also, I had a friend—a friend who for many years never left my side. Occasionally of an imbecility to make one afraid, nevertheless he was very dear to me. Figure to yourself that I miss even his stupidity. His naïveté, his honest outlook, the pleasure of delighting and surprising him by my superior gifts—all these I miss more than I can tell you.”

“He died?” I asked sympathetically.

“Not so. He lives and flourishes—but on the other side of the world. He is now in the Argentine.”

“In the Argentine,” I said enviously.

22

I have always wanted to go to South America. I sighed, and then looked up to find Mr. Porrott eyeing me sympathetically. He seemed an understanding little man.

“You will go there, yes?” he asked.

I shook my head with a sigh.

“I could have gone,” I said, “a year ago. But I was foolish—and worse than foolish—greedy. I risked the substance for the shadow.”

“I comprehend,” said Mr. Porrott. “You speculated?”

I nodded mournfully, but in spite of myself I felt secretly entertained. This ridiculous little man was so portentously solemn.

“Not the Porcupine Oilfields?” he asked suddenly.

I stared.

“I thought of them, as a matter of fact, but in the end I plumped for a gold mine in Western Australia.”

My neighbor was regarding me with a strange expression which I could not fathom.

“It is Fate,” he said at last.

“What is Fate?” I asked irritably.

“That I should live next to a man who seriously considers Porcupine Oilfields, and also West Australian Gold Mines. Tell me, have you also a penchant for auburn hair?”

I stared at him open-mouthed, and he burst out laughing.

“No, no, it is not the insanity that I suffer from. Make your mind easy. It was a foolish question that I put to you there, for, see you, my friend of whom I spoke was23 a young man, a man who thought all women good, and most of them beautiful. But you are a man of middle age, a doctor, a man who knows the folly and the vanity of most things in this life of ours. Well, well, we are neighbors. I beg of you to accept and present to your excellent sister my best marrow.”

He stooped, and with a flourish produced an immense specimen of the tribe, which I duly accepted in the spirit in which it was offered.

“Indeed,” said the little man cheerfully, “this has not been a wasted morning. I have made the acquaintance of a man who in some ways resembles my far-off friend. By the way, I should like to ask you a question. You doubtless know every one in this tiny village. Who is the young man with the very dark hair and eyes, and the handsome face. He walks with his head flung back, and an easy smile on his lips?”

The description left me in no doubt.

“That must be Captain Ralph Paton,” I said slowly.

“I have not seen him about here before?”

“No, he has not been here for some time. But he is the son—adopted son, rather—of Mr. Ackroyd of Fernly Park.”

My neighbor made a slight gesture of impatience.

“Of course, I should have guessed. Mr. Ackroyd spoke of him many times.”

“You know Mr. Ackroyd?” I said, slightly surprised.

“Mr. Ackroyd knew me in London—when I was at work there. I have asked him to say nothing of my profession down here.”

24

“I see,” I said, rather amused by this patent snobbery, as I thought it.

But the little man went on with an almost grandiloquent smirk.

“One prefers to remain incognito. I am not anxious for notoriety. I have not even troubled to correct the local version of my name.”

“Indeed,” I said, not knowing quite what to say.

“Captain Ralph Paton,” mused Mr. Porrott. “And so he is engaged to Mr. Ackroyd’s niece, the charming Miss Flora.”

“Who told you so?” I asked, very much surprised.

“Mr. Ackroyd. About a week ago. He is very pleased about it—has long desired that such a thing should come to pass, or so I understood from him. I even believe that he brought some pressure to bear upon the young man. That is never wise. A young man should marry to please himself—not to please a stepfather from whom he has expectations.”

My ideas were completely upset. I could not see Ackroyd taking a hairdresser into his confidence, and discussing the marriage of his niece and stepson with him. Ackroyd extends a genial patronage to the lower orders, but he has a very great sense of his own dignity. I began to think that Porrott couldn’t be a hairdresser after all.

To hide my confusion, I said the first thing that came into my head.

“What made you notice Ralph Paton? His good looks?”

“No, not that alone—though he is unusually good-looking25 for an Englishman—what your lady novelists would call a Greek God. No, there was something about that young man that I did not understand.”

He said the last sentence in a musing tone of voice which made an indefinable impression upon me. It was as though he was summing up the boy by the light of some inner knowledge that I did not share. It was that impression that was left with me, for at that moment my sister’s voice called me from the house.

I went in. Caroline had her hat on, and had evidently just come in from the village. She began without preamble.

“I met Mr. Ackroyd.”

“Yes?” I said.

“I stopped him, of course, but he seemed in a great hurry, and anxious to get away.”

I have no doubt but that that was the case. He would feel towards Caroline much as he had felt towards Miss Ganett earlier in the day—perhaps more so. Caroline is less easy to shake off.

“I asked him at once about Ralph. He was absolutely astonished. Had no idea the boy was down here. He actually said he thought I must have made a mistake. I! A mistake!”

“Ridiculous,” I said. “He ought to have known you better.”

“Then he went on to tell me that Ralph and Flora are engaged.”

“I know that too,” I interrupted, with modest pride.

“Who told you?”

26

“Our new neighbor.”

Caroline visibly wavered for a second or two, much as a roulette ball might coyly hover between two numbers. Then she declined the tempting red herring.

“I told Mr. Ackroyd that Ralph was staying at the Three Boars.”

“Caroline,” I said, “do you never reflect that you might do a lot of harm with this habit of yours of repeating everything indiscriminately?”

“Nonsense,” said my sister. “People ought to know things. I consider it my duty to tell them. Mr. Ackroyd was very grateful to me.”

“Well?” I said, for there was clearly more to come.

“I think he went straight off to the Three Boars, but if so he didn’t find Ralph there.”

“No?”

“No. Because as I was coming back through the wood——”

“Coming back through the wood?” I interrupted.

Caroline had the grace to blush.

“It was such a lovely day,” she exclaimed. “I thought I would make a little round. The woods with their autumnal tints are so perfect at this time of year.”

Caroline does not care a hang for woods at any time of year. Normally she regards them as places where you get your feet damp, and where all kinds of unpleasant things may drop on your head. No, it was good sound mongoose instinct which took her to our local wood. It is the only place adjacent to the village of King’s Abbot27 where you can talk with a young woman unseen by the whole of the village. It adjoins the Park of Fernly.

“Well,” I said, “go on.”

“As I say, I was just coming back through the wood when I heard voices.”

Caroline paused.

“Yes?”

“One was Ralph Paton’s—I knew it at once. The other was a girl’s. Of course I didn’t mean to listen——”

“Of course not,” I interjected, with patent sarcasm—which was, however, wasted on Caroline.

“But I simply couldn’t help overhearing. The girl said something—I didn’t quite catch what it was, and Ralph answered. He sounded very angry. ‘My dear girl,’ he said. ‘Don’t you realize that it is quite on the cards the old man will cut me off with a shilling? He’s been pretty fed up with me for the last few years. A little more would do it. And we need the dibs, my dear. I shall be a very rich man when the old fellow pops off. He’s mean as they make ’em, but he’s rolling in money really. I don’t want him to go altering his will. You leave it to me, and don’t worry.’ Those were his exact words. I remember them perfectly. Unfortunately, just then I stepped on a dry twig or something, and they lowered their voices and moved away. I couldn’t, of course, go rushing after them, so wasn’t able to see who the girl was.”

“That must have been most vexing,” I said. “I suppose, though, you hurried on to the Three Boars, felt28 faint, and went into the bar for a glass of brandy, and so were able to see if both the barmaids were on duty?”

“It wasn’t a barmaid,” said Caroline unhesitatingly. “In fact, I’m almost sure that it was Flora Ackroyd, only——”

“Only it doesn’t seem to make sense,” I agreed.

“But if it wasn’t Flora, who could it have been?”

Rapidly my sister ran over a list of maidens living in the neighborhood, with profuse reasons for and against.

When she paused for breath, I murmured something about a patient, and slipped out.

I proposed to make my way to the Three Boars. It seemed likely that Ralph Paton would have returned there by now.

I knew Ralph very well—better, perhaps, than any one else in King’s Abbot, for I had known his mother before him, and therefore I understood much in him that puzzled others. He was, to a certain extent, the victim of heredity. He had not inherited his mother’s fatal propensity for drink, but nevertheless he had in him a strain of weakness. As my new friend of this morning had declared, he was extraordinarily handsome. Just on six feet, perfectly proportioned, with the easy grace of an athlete, he was dark, like his mother, with a handsome, sunburnt face always ready to break into a smile. Ralph Paton was of those born to charm easily and without effort. He was self-indulgent and extravagant, with no veneration for anything on earth, but he was lovable nevertheless, and his friends were all devoted to him.

Could I do anything with the boy? I thought I could.

29

On inquiry at the Three Boars I found that Captain Paton had just come in. I went up to his room and entered unannounced.

For a moment, remembering what I had heard and seen, I was doubtful of my reception, but I need have had no misgivings.

“Why, it’s Sheppard! Glad to see you.”

He came forward to meet me, hand outstretched, a sunny smile lighting up his face.

“The one person I am glad to see in this infernal place.”

I raised my eyebrows.

“What’s the place been doing?”

He gave a vexed laugh.

“It’s a long story. Things haven’t been going well with me, doctor. But have a drink, won’t you?”

“Thanks,” I said, “I will.”

He pressed the bell, then, coming back, threw himself into a chair.

“Not to mince matters,” he said gloomily, “I’m in the devil of a mess. In fact, I haven’t the least idea what to do next.”

“What’s the matter?” I asked sympathetically.

“It’s my confounded stepfather.”

“What has he done?”

“It isn’t what he’s done yet, but what he’s likely to do.”

The bell was answered, and Ralph ordered the drinks. When the man had gone again, he sat hunched in the arm-chair, frowning to himself.

30

“Is it really—serious?” I asked.

He nodded.

“I’m fairly up against it this time,” he said soberly.

The unusual ring of gravity in his voice told me that he spoke the truth. It took a good deal to make Ralph grave.

“In fact,” he continued, “I can’t see my way ahead.... I’m damned if I can.”

“If I could help——” I suggested diffidently.

But he shook his head very decidedly.

“Good of you, doctor. But I can’t let you in on this. I’ve got to play a lone hand.”

He was silent a minute and then repeated in a slightly different tone of voice:—

“Yes—I’ve got to play a lone hand....”

CHAPTER IV

It was just a few minutes before half-past seven when I rang the front door bell of Fernly Park. The door was opened with admirable promptitude by Parker, the butler.

The night was such a fine one that I had preferred to come on foot. I stepped into the big square hall and Parker relieved me of my overcoat. Just then Ackroyd’s secretary, a pleasant young fellow by the name of Raymond, passed through the hall on his way to Ackroyd’s study, his hands full of papers.

“Good-evening, doctor. Coming to dine? Or is this a professional call?”

The last was in allusion to my black bag, which I had laid down on the oak chest.

I explained that I expected a summons to a confinement case at any moment, and so had come out prepared for an emergency call. Raymond nodded, and went on his way, calling over his shoulder:—

“Go into the drawing-room. You know the way. The ladies will be down in a minute. I must just take these papers to Mr. Ackroyd, and I’ll tell him you’re here.”

On Raymond’s appearance Parker had withdrawn, so I was alone in the hall. I settled my tie, glanced in a large mirror which hung there, and crossed to the door32 directly facing me, which was, as I knew, the door of the drawing-room.

I noticed, just as I was turning the handle, a sound from within—the shutting down of a window, I took it to be. I noted it, I may say, quite mechanically, without attaching any importance to it at the time.

I opened the door and walked in. As I did so, I almost collided with Miss Russell, who was just coming out. We both apologized.

For the first time I found myself appraising the housekeeper and thinking what a handsome woman she must once have been—indeed, as far as that goes, still was. Her dark hair was unstreaked with gray, and when she had a color, as she had at this minute, the stern quality of her looks was not so apparent.

Quite subconsciously I wondered whether she had been out, for she was breathing hard, as though she had been running.

“I’m afraid I’m a few minutes early,” I said.

“Oh! I don’t think so. It’s gone half-past seven, Dr. Sheppard.” She paused a minute before saying, “I—didn’t know you were expected to dinner to-night. Mr. Ackroyd didn’t mention it.”

I received a vague impression that my dining there displeased her in some way, but I couldn’t imagine why.

“How’s the knee?” I inquired.

“Much the same, thank you, doctor. I must be going now. Mrs. Ackroyd will be down in a moment. I—I only came in here to see if the flowers were all right.”

She passed quickly out of the room. I strolled to the33 window, wondering at her evident desire to justify her presence in the room. As I did so, I saw what, of course, I might have known all the time had I troubled to give my mind to it, namely, that the windows were long French ones opening on the terrace. The sound I had heard, therefore, could not have been that of a window being shut down.

Quite idly, and more to distract my mind from painful thoughts than for any other reason, I amused myself by trying to guess what could have caused the sound in question.

Coals on the fire? No, that was not the kind of noise at all. A drawer of the bureau pushed in? No, not that.

Then my eye was caught by what, I believe, is called a silver table, the lid of which lifts, and through the glass of which you can see the contents. I crossed over to it, studying the things. There were one or two pieces of old silver, a baby shoe belonging to King Charles the First, some Chinese jade figures, and quite a number of African implements and curios. Wanting to examine one of the jade figures more closely, I lifted the lid. It slipped through my fingers and fell.

At once I recognized the sound I had heard. It was this same table lid being shut down gently and carefully. I repeated the action once or twice for my own satisfaction. Then I lifted the lid to scrutinize the contents more closely.

I was still bending over the open silver table when Flora Ackroyd came into the room.

Quite a lot of people do not like Flora Ackroyd, but34 nobody can help admiring her. And to her friends she can be very charming. The first thing that strikes you about her is her extraordinary fairness. She has the real Scandinavian pale gold hair. Her eyes are blue—blue as the waters of a Norwegian fiord, and her skin is cream and roses. She has square, boyish shoulders and slight hips. And to a jaded medical man it is very refreshing to come across such perfect health.

A simple straight-forward English girl—I may be old-fashioned, but I think the genuine article takes a lot of beating.

Flora joined me by the silver table, and expressed heretical doubts as to King Charles I ever having worn the baby shoe.

“And anyway,” continued Miss Flora, “all this making a fuss about things because some one wore or used them seems to me all nonsense. They’re not wearing or using them now. The pen that George Eliot wrote The Mill on the Floss with—that sort of thing—well, it’s only just a pen after all. If you’re really keen on George Eliot, why not get The Mill on the Floss in a cheap edition and read it.”

“I suppose you never read such old out-of-date stuff, Miss Flora?”

“You’re wrong, Dr. Sheppard. I love The Mill on the Floss.”

I was rather pleased to hear it. The things young women read nowadays and profess to enjoy positively frighten me.

“You haven’t congratulated me yet, Dr. Sheppard,” said Flora. “Haven’t you heard?”

35

She held out her left hand. On the third finger of it was an exquisitely set single pearl.

“I’m going to marry Ralph, you know,” she went on. “Uncle is very pleased. It keeps me in the family, you see.”

I took both her hands in mine.

“My dear,” I said, “I hope you’ll be very happy.”

“We’ve been engaged for about a month,” continued Flora in her cool voice, “but it was only announced yesterday. Uncle is going to do up Cross-stones, and give it to us to live in, and we’re going to pretend to farm. Really, we shall hunt all the winter, town for the season, and then go yachting. I love the sea. And, of course, I shall take a great interest in the parish affairs, and attend all the Mothers’ Meetings.”

Just then Mrs. Ackroyd rustled in, full of apologies for being late.

I am sorry to say I detest Mrs. Ackroyd. She is all chains and teeth and bones. A most unpleasant woman. She has small pale flinty blue eyes, and however gushing her words may be, those eyes of hers always remain coldly speculative.

I went across to her, leaving Flora by the window. She gave me a handful of assorted knuckles and rings to squeeze, and began talking volubly.

Had I heard about Flora’s engagement? So suitable in every way. The dear young things had fallen in love at first sight. Such a perfect pair, he so dark and she so fair.

“I can’t tell you, my dear Dr. Sheppard, the relief to a mother’s heart.”

36

Mrs. Ackroyd sighed—a tribute to her mother’s heart, whilst her eyes remained shrewdly observant of me.

“I was wondering. You are such an old friend of dear Roger’s. We know how much he trusts to your judgment. So difficult for me—in my position, as poor Cecil’s widow. But there are so many tiresome things—settlements, you know—all that. I fully believe that Roger intends to make settlements upon dear Flora, but, as you know, he is just a leetle peculiar about money. Very usual, I’ve heard, amongst men who are captains of industry. I wondered, you know, if you could just sound him on the subject? Flora is so fond of you. We feel you are quite an old friend, although we have only really known you just over two years.”

Mrs. Ackroyd’s eloquence was cut short as the drawing-room door opened once more. I was pleased at the interruption. I hate interfering in other people’s affairs, and I had not the least intention of tackling Ackroyd on the subject of Flora’s settlements. In another moment I should have been forced to tell Mrs. Ackroyd as much.

“You know Major Blunt, don’t you, doctor?”

“Yes, indeed,” I said.

A lot of people know Hector Blunt—at least by repute. He has shot more wild animals in unlikely places than any man living, I suppose. When you mention him, people say: “Blunt—you don’t mean the big game man, do you?”

His friendship with Ackroyd has always puzzled me a little. The two men are so totally dissimilar. Hector Blunt is perhaps five years Ackroyd’s junior. They made37 friends early in life, and though their ways have diverged, the friendship still holds. About once in two years Blunt spends a fortnight at Fernly, and an immense animal’s head, with an amazing number of horns which fixes you with a glazed stare as soon as you come inside the front door, is a permanent reminder of the friendship.

Blunt had entered the room now with his own peculiar, deliberate, yet soft-footed tread. He is a man of medium height, sturdily and rather stockily built. His face is almost mahogany-colored, and is peculiarly expressionless. He has gray eyes that give the impression of always watching something that is happening very far away. He talks little, and what he does say is said jerkily, as though the words were forced out of him unwillingly.

He said now: “How are you, Sheppard?” in his usual abrupt fashion, and then stood squarely in front of the fireplace looking over our heads as though he saw something very interesting happening in Timbuctoo.

“Major Blunt,” said Flora, “I wish you’d tell me about these African things. I’m sure you know what they all are.”

I have heard Hector Blunt described as a woman hater, but I noticed that he joined Flora at the silver table with what might be described as alacrity. They bent over it together.

I was afraid Mrs. Ackroyd would begin talking about settlements again, so I made a few hurried remarks about the new sweet pea. I knew there was a new sweet pea because the Daily Mail had told me so that morning.38 Mrs. Ackroyd knows nothing about horticulture, but she is the kind of woman who likes to appear well-informed about the topics of the day, and she, too, reads the Daily Mail. We were able to converse quite intelligently until Ackroyd and his secretary joined us, and immediately afterwards Parker announced dinner.

My place at table was between Mrs. Ackroyd and Flora. Blunt was on Mrs. Ackroyd’s other side, and Geoffrey Raymond next to him.

Dinner was not a cheerful affair. Ackroyd was visibly preoccupied. He looked wretched, and ate next to nothing. Mrs. Ackroyd, Raymond, and I kept the conversation going. Flora seemed affected by her uncle’s depression, and Blunt relapsed into his usual taciturnity.

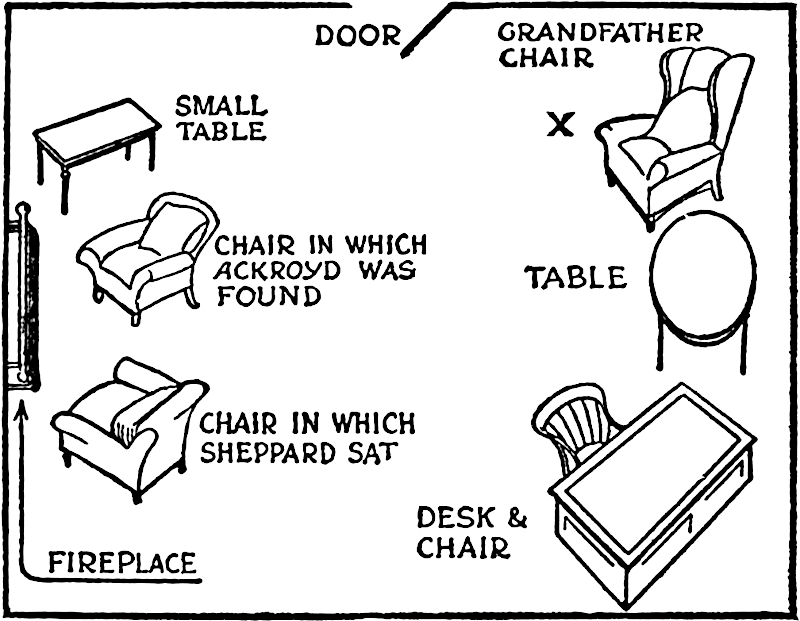

Immediately after dinner Ackroyd slipped his arm through mine and led me off to his study.

“Once we’ve had coffee, we shan’t be disturbed again,” he explained. “I told Raymond to see to it that we shouldn’t be interrupted.”

I studied him quietly without appearing to do so. He was clearly under the influence of some strong excitement. For a minute or two he paced up and down the room, then, as Parker entered with the coffee tray, he sank into an arm-chair in front of the fire.

The study was a comfortable apartment. Book-shelves lined one wall of it. The chairs were big and covered in dark blue leather. A large desk stood by the window and was covered with papers neatly docketed and filed. On a round table were various magazines and sporting papers.

39

“I’ve had a return of that pain after food lately,” remarked Ackroyd casually, as he helped himself to coffee. “You must give me some more of those tablets of yours.”

It struck me that he was anxious to convey the impression that our conference was a medical one. I played up accordingly.

“I thought as much. I brought some up with me.”

“Good man. Hand them over now.”

“They’re in my bag in the hall. I’ll get them.”

Ackroyd arrested me.

“Don’t you trouble. Parker will get them. Bring in the doctor’s bag, will you, Parker?”

“Very good, sir.”

Parker withdrew. As I was about to speak, Ackroyd threw up his hand.

“Not yet. Wait. Don’t you see I’m in such a state of nerves that I can hardly contain myself?”

I saw that plainly enough. And I was very uneasy. All sorts of forebodings assailed me.

Ackroyd spoke again almost immediately.

“Make certain that window’s closed, will you?” he asked.

Somewhat surprised, I got up and went to it. It was not a French window, but one of the ordinary sash type. The heavy blue velvet curtains were drawn in front of it, but the window itself was open at the top.

Parker reëntered the room with my bag while I was still at the window.

“That’s all right,” I said, emerging again into the room.

40

“You’ve put the latch across?”

“Yes, yes. What’s the matter with you, Ackroyd?”

The door had just closed behind Parker, or I would not have put the question.

Ackroyd waited just a minute before replying.

“I’m in hell,” he said slowly, after a minute. “No, don’t bother with those damned tablets. I only said that for Parker. Servants are so curious. Come here and sit down. The door’s closed too, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Nobody can overhear; don’t be uneasy.”

“Sheppard, nobody knows what I’ve gone through in the last twenty-four hours. If a man’s house ever fell in ruins about him, mine has about me. This business of Ralph’s is the last straw. But we won’t talk about that now. It’s the other—the other——! I don’t know what to do about it. And I’ve got to make up my mind soon.”

“What’s the trouble?”

Ackroyd remained silent for a minute or two. He seemed curiously averse to begin. When he did speak, the question he asked came as a complete surprise. It was the last thing I expected.

“Sheppard, you attended Ashley Ferrars in his last illness, didn’t you?”

“Yes, I did.”

He seemed to find even greater difficulty in framing his next question.

“Did you never suspect—did it ever enter your head—that—well, that he might have been poisoned?”

I was silent for a minute or two. Then I made up my mind what to say. Roger Ackroyd was not Caroline.

41

“I’ll tell you the truth,” I said. “At the time I had no suspicion whatever, but since—well, it was mere idle talk on my sister’s part that first put the idea into my head. Since then I haven’t been able to get it out again. But, mind you, I’ve no foundation whatever for that suspicion.”

“He was poisoned,” said Ackroyd.

He spoke in a dull heavy voice.

“Who by?” I asked sharply.

“His wife.”

“How do you know that?”

“She told me so herself.”

“When?”

“Yesterday! My God! yesterday! It seems ten years ago.”

I waited a minute, and then he went on.

“You understand, Sheppard, I’m telling you this in confidence. It’s to go no further. I want your advice—I can’t carry the whole weight by myself. As I said just now, I don’t know what to do.”

“Can you tell me the whole story?” I said. “I’m still in the dark. How did Mrs. Ferrars come to make this confession to you?”

“It’s like this. Three months ago I asked Mrs. Ferrars to marry me. She refused. I asked her again and she consented, but she refused to allow me to make the engagement public until her year of mourning was up. Yesterday I called upon her, pointed out that a year and three weeks had now elapsed since her husband’s death, and that there could be no further objection to making the42 engagement public property. I had noticed that she had been very strange in her manner for some days. Now, suddenly, without the least warning, she broke down completely. She—she told me everything. Her hatred of her brute of a husband, her growing love for me, and the—the dreadful means she had taken. Poison! My God! It was murder in cold blood.”

I saw the repulsion, the horror, in Ackroyd’s face. So Mrs. Ferrars must have seen it. Ackroyd is not the type of the great lover who can forgive all for love’s sake. He is fundamentally a good citizen. All that was sound and wholesome and law-abiding in him must have turned from her utterly in that moment of revelation.

“Yes,” he went on, in a low, monotonous voice, “she confessed everything. It seems that there is one person who has known all along—who has been blackmailing her for huge sums. It was the strain of that that drove her nearly mad.”

“Who was the man?”

Suddenly before my eyes there arose the picture of Ralph Paton and Mrs. Ferrars side by side. Their heads so close together. I felt a momentary throb of anxiety. Supposing—oh! but surely that was impossible. I remembered the frankness of Ralph’s greeting that very afternoon. Absurd!

“She wouldn’t tell me his name,” said Ackroyd slowly. “As a matter of fact, she didn’t actually say that it was a man. But of course——”

“Of course,” I agreed. “It must have been a man. And you’ve no suspicion at all?”

43

For answer Ackroyd groaned and dropped his head into his hands.

“It can’t be,” he said. “I’m mad even to think of such a thing. No, I won’t even admit to you the wild suspicion that crossed my mind. I’ll tell you this much, though. Something she said made me think that the person in question might be actually among my household—but that can’t be so. I must have misunderstood her.”

“What did you say to her?” I asked.

“What could I say? She saw, of course, the awful shock it had been to me. And then there was the question, what was my duty in the matter? She had made me, you see, an accessory after the fact. She saw all that, I think, quicker than I did. I was stunned, you know. She asked me for twenty-four hours—made me promise to do nothing till the end of that time. And she steadfastly refused to give me the name of the scoundrel who had been blackmailing her. I suppose she was afraid that I might go straight off and hammer him, and then the fat would have been in the fire as far as she was concerned. She told me that I should hear from her before twenty-four hours had passed. My God! I swear to you, Sheppard, that it never entered my head what she meant to do. Suicide! And I drove her to it.”

“No, no,” I said. “Don’t take an exaggerated view of things. The responsibility for her death doesn’t lie at your door.”

“The question is, what am I to do now? The poor lady is dead. Why rake up past trouble?”

“I rather agree with you,” I said.

44

“But there’s another point. How am I to get hold of that scoundrel who drove her to death as surely as if he’d killed her. He knew of the first crime, and he fastened on to it like some obscene vulture. She’s paid the penalty. Is he to go scot-free?”

“I see,” I said slowly. “You want to hunt him down? It will mean a lot of publicity, you know.”

“Yes, I’ve thought of that. I’ve zigzagged to and fro in my mind.”

“I agree with you that the villain ought to be punished, but the cost has got to be reckoned.”

Ackroyd rose and walked up and down. Presently he sank into the chair again.

“Look here, Sheppard, suppose we leave it like this. If no word comes from her, we’ll let the dead things lie.”

“What do you mean by word coming from her?” I asked curiously.

“I have the strongest impression that somewhere or somehow she must have left a message for me—before she went. I can’t argue about it, but there it is.”

I shook my head.

“She left no letter or word of any kind. I asked.”

“Sheppard, I’m convinced that she did. And more, I’ve a feeling that by deliberately choosing death, she wanted the whole thing to come out, if only to be revenged on the man who drove her to desperation. I believe that if I could have seen her then, she would have told me his name and bid me go for him for all I was worth.”

He looked at me.

45

“You don’t believe in impressions?”

“Oh, yes, I do, in a sense. If, as you put it, word should come from her——”

I broke off. The door opened noiselessly and Parker entered with a salver on which were some letters.

“The evening post, sir,” he said, handing the salver to Ackroyd.

Then he collected the coffee cups and withdrew.

My attention, diverted for a moment, came back to Ackroyd. He was staring like a man turned to stone at a long blue envelope. The other letters he had let drop to the ground.

“Her writing,” he said in a whisper. “She must have gone out and posted it last night, just before—before——”

He ripped open the envelope and drew out a thick enclosure. Then he looked up sharply.

“You’re sure you shut the window?” he said.

“Quite sure,” I said, surprised. “Why?”

“All this evening I’ve had a queer feeling of being watched, spied upon. What’s that——?”

He turned sharply. So did I. We both had the impression of hearing the latch of the door give ever so slightly. I went across to it and opened it. There was no one there.

“Nerves,” murmured Ackroyd to himself.

He unfolded the thick sheets of paper, and read aloud in a low voice.

46

“My dear, my very dear Roger,—A life calls for a life. I see that—I saw it in your face this afternoon. So I am taking the only road open to me. I leave to you the punishment of the person who has made my life a hell upon earth for the last year. I would not tell you the name this afternoon, but I propose to write it to you now. I have no children or near relations to be spared, so do not fear publicity. If you can, Roger, my very dear Roger, forgive me the wrong I meant to do you, since when the time came, I could not do it after all....”

Ackroyd, his finger on the sheet to turn it over, paused.

“Sheppard, forgive me, but I must read this alone,” he said unsteadily. “It was meant for my eyes, and my eyes only.”

He put the letter in the envelope and laid it on the table.

“Later, when I am alone.”

“No,” I cried impulsively, “read it now.”

Ackroyd stared at me in some surprise.

“I beg your pardon,” I said, reddening. “I do not mean read it aloud to me. But read it through whilst I am still here.”

Ackroyd shook his head.

“No, I’d rather wait.”

But for some reason, obscure to myself, I continued to urge him.

“At least, read the name of the man,” I said.

Now Ackroyd is essentially pig-headed. The more you urge him to do a thing, the more determined he is not to do it. All my arguments were in vain.

47

The letter had been brought in at twenty minutes to nine. It was just on ten minutes to nine when I left him, the letter still unread. I hesitated with my hand on the door handle, looking back and wondering if there was anything I had left undone. I could think of nothing. With a shake of the head I passed out and closed the door behind me.

I was startled by seeing the figure of Parker close at hand. He looked embarrassed, and it occurred to me that he might have been listening at the door.

What a fat, smug, oily face the man had, and surely there was something decidedly shifty in his eye.

“Mr. Ackroyd particularly does not want to be disturbed,” I said coldly. “He told me to tell you so.”

“Quite so, sir. I—I fancied I heard the bell ring.”

This was such a palpable untruth that I did not trouble to reply. Preceding me to the hall, Parker helped me on with my overcoat, and I stepped out into the night. The moon was overcast and everything seemed very dark and still. The village church clock chimed nine o’clock as I passed through the lodge gates. I turned to the left towards the village, and almost cannoned into a man coming in the opposite direction.

“This the way to Fernly Park, mister?” asked the stranger in a hoarse voice.

I looked at him. He was wearing a hat pulled down over his eyes, and his coat collar turned up. I could see little or nothing of his face, but he seemed a young fellow. The voice was rough and uneducated.

“These are the lodge gates here,” I said.

48

“Thank you, mister.” He paused, and then added, quite unnecessarily, “I’m a stranger in these parts, you see.”

He went on, passing through the gates as I turned to look after him.

The odd thing was that his voice reminded me of some one’s voice that I knew, but whose it was I could not think.

Ten minutes later I was at home once more. Caroline was full of curiosity to know why I had returned so early. I had to make up a slightly fictitious account of the evening in order to satisfy her, and I had an uneasy feeling that she saw through the transparent device.

At ten o’clock I rose, yawned, and suggested bed. Caroline acquiesced.

It was Friday night, and on Friday night I wind the clocks. I did it as usual, whilst Caroline satisfied herself that the servants had locked up the kitchen properly.

It was a quarter past ten as we went up the stairs. I had just reached the top when the telephone rang in the hall below.

“Mrs. Bates,” said Caroline immediately.

“I’m afraid so,” I said ruefully.

I ran down the stairs and took up the receiver.

“What?” I said. “What? Certainly, I’ll come at once.”

I ran upstairs, caught up my bag, and stuffed a few extra dressings into it.

“Parker telephoning,” I shouted to Caroline, “from Fernly. They’ve just found Roger Ackroyd murdered.”

CHAPTER V

I got out the car in next to no time, and drove rapidly to Fernly. Jumping out, I pulled the bell impatiently. There was some delay in answering, and I rang again.

Then I heard the rattle of the chain and Parker, his impassivity of countenance quite unmoved, stood in the open doorway.

I pushed past him into the hall.

“Where is he?” I demanded sharply.

“I beg your pardon, sir?”

“Your master. Mr. Ackroyd. Don’t stand there staring at me, man. Have you notified the police?”

“The police, sir? Did you say the police?” Parker stared at me as though I were a ghost.

“What’s the matter with you, Parker? If, as you say, your master has been murdered——”

A gasp broke from Parker.

“The master? Murdered? Impossible, sir!”

It was my turn to stare.

“Didn’t you telephone to me, not five minutes ago, and tell me that Mr. Ackroyd had been found murdered?”

“Me, sir? Oh! no indeed, sir. I wouldn’t dream of doing such a thing.”

“Do you mean to say it’s all a hoax? That there’s nothing the matter with Mr. Ackroyd?”

50

“Excuse me, sir, did the person telephoning use my name?”

“I’ll give you the exact words I heard. ‘Is that Dr. Sheppard? Parker, the butler at Fernly, speaking. Will you please come at once, sir. Mr. Ackroyd has been murdered.’”

Parker and I stared at each other blankly.

“A very wicked joke to play, sir,” he said at last, in a shocked tone. “Fancy saying a thing like that.”

“Where is Mr. Ackroyd?” I asked suddenly.

“Still in the study, I fancy, sir. The ladies have gone to bed, and Major Blunt and Mr. Raymond are in the billiard room.”

“I think I’ll just look in and see him for a minute,” I said. “I know he didn’t want to be disturbed again, but this odd practical joke has made me uneasy. I’d just like to satisfy myself that he’s all right.”

“Quite so, sir. It makes me feel quite uneasy myself. If you don’t object to my accompanying you as far as the door, sir——?”

“Not at all,” I said. “Come along.”

I passed through the door on the right, Parker on my heels, traversed the little lobby where a small flight of stairs led upstairs to Ackroyd’s bedroom, and tapped on the study door.

There was no answer. I turned the handle, but the door was locked.

“Allow me, sir,” said Parker.

Very nimbly, for a man of his build, he dropped on one knee and applied his eye to the keyhole.

51

“Key is in the lock all right, sir,” he said, rising. “On the inside. Mr. Ackroyd must have locked himself in and possibly just dropped off to sleep.”

I bent down and verified Parker’s statement.

“It seems all right,” I said, “but, all the same, Parker, I’m going to wake your master up. I shouldn’t be satisfied to go home without hearing from his own lips that he’s quite all right.”

So saying, I rattled the handle and called out, “Ackroyd, Ackroyd, just a minute.”

But still there was no answer. I glanced over my shoulder.

“I don’t want to alarm the household,” I said hesitatingly.

Parker went across and shut the door from the big hall through which we had come.

“I think that will be all right now, sir. The billiard room is at the other side of the house, and so are the kitchen quarters and the ladies’ bedrooms.”

I nodded comprehendingly. Then I banged once more frantically on the door, and stooping down, fairly bawled through the keyhole:—

“Ackroyd, Ackroyd! It’s Sheppard. Let me in.”

And still—silence. Not a sign of life from within the locked room. Parker and I glanced at each other.

“Look here, Parker,” I said, “I’m going to break this door in—or rather, we are. I’ll take the responsibility.”

“If you say so, sir,” said Parker, rather doubtfully.

“I do say so. I’m seriously alarmed about Mr. Ackroyd.”

52

I looked round the small lobby and picked up a heavy oak chair. Parker and I held it between us and advanced to the assault. Once, twice, and three times we hurled it against the lock. At the third blow it gave, and we staggered into the room.

Ackroyd was sitting as I had left him in the arm-chair before the fire. His head had fallen sideways, and clearly visible, just below the collar of his coat, was a shining piece of twisted metalwork.

Parker and I advanced till we stood over the recumbent figure. I heard the butler draw in his breath with a sharp hiss.

“Stabbed from be’ind,” he murmured. “’Orrible!”

He wiped his moist brow with his handkerchief, then stretched out a hand gingerly towards the hilt of the dagger.

“You mustn’t touch that,” I said sharply. “Go at once to the telephone and ring up the police station. Inform them of what has happened. Then tell Mr. Raymond and Major Blunt.”

“Very good, sir.”

Parker hurried away, still wiping his perspiring brow.

I did what little had to be done. I was careful not to disturb the position of the body, and not to handle the dagger at all. No object was to be attained by moving it. Ackroyd had clearly been dead some little time.

Then I heard young Raymond’s voice, horror-stricken and incredulous, outside.

“What do you say? Oh! impossible! Where’s the doctor?”

53

He appeared impetuously in the doorway, then stopped dead, his face very white. A hand put him aside, and Hector Blunt came past him into the room.

“My God!” said Raymond from behind him; “it’s true, then.”

Blunt came straight on till he reached the chair. He bent over the body, and I thought that, like Parker, he was going to lay hold of the dagger hilt. I drew him back with one hand.

“Nothing must be moved,” I explained. “The police must see him exactly as he is now.”

Blunt nodded in instant comprehension. His face was expressionless as ever, but I thought I detected signs of emotion beneath the stolid mask. Geoffrey Raymond had joined us now, and stood peering over Blunt’s shoulder at the body.

“This is terrible,” he said in a low voice.

He had regained his composure, but as he took off the pince-nez he habitually wore and polished them I observed that his hand was shaking.

“Robbery, I suppose,” he said. “How did the fellow get in? Through the window? Has anything been taken?”

He went towards the desk.

“You think it’s burglary?” I said slowly.

“What else could it be? There’s no question of suicide, I suppose?”

“No man could stab himself in such a way,” I said confidently. “It’s murder right enough. But with what motive?”

54

“Roger hadn’t an enemy in the world,” said Blunt quietly. “Must have been burglars. But what was the thief after? Nothing seems to be disarranged?”

He looked round the room. Raymond was still sorting the papers on the desk.

“There seems nothing missing, and none of the drawers show signs of having been tampered with,” the secretary observed at last. “It’s very mysterious.”

Blunt made a slight motion with his head.

“There are some letters on the floor here,” he said.

I looked down. Three or four letters still lay where Ackroyd had dropped them earlier in the evening.

But the blue envelope containing Mrs. Ferrars’s letter had disappeared. I half opened my mouth to speak, but at that moment the sound of a bell pealed through the house. There was a confused murmur of voices in the hall, and then Parker appeared with our local inspector and a police constable.

“Good evening, gentlemen,” said the inspector. “I’m terribly sorry for this! A good kind gentleman like Mr. Ackroyd. The butler says it is murder. No possibility of accident or suicide, doctor?”

“None whatever,” I said.

“Ah! A bad business.”

He came and stood over the body.

“Been moved at all?” he asked sharply.

“Beyond making certain that life was extinct—an easy matter—I have not disturbed the body in any way.”

“Ah! And everything points to the murderer having55 got clear away—for the moment, that is. Now then, let me hear all about it. Who found the body?”

I explained the circumstances carefully.

“A telephone message, you say? From the butler?”

“A message that I never sent,” declared Parker earnestly. “I’ve not been near the telephone the whole evening. The others can bear me out that I haven’t.”

“Very odd, that. Did it sound like Parker’s voice, doctor?”

“Well—I can’t say I noticed. I took it for granted, you see.”

“Naturally. Well, you got up here, broke in the door, and found poor Mr. Ackroyd like this. How long should you say he had been dead, doctor?”

“Half an hour at least—perhaps longer,” I said.

“The door was locked on the inside, you say? What about the window?”

“I myself closed and bolted it earlier in the evening at Mr. Ackroyd’s request.”

The inspector strode across to it and threw back the curtains.

“Well, it’s open now anyway,” he remarked.

True enough, the window was open, the lower sash being raised to its fullest extent.

The inspector produced a pocket torch and flashed it along the sill outside.

“This is the way he went all right,” he remarked, “and got in. See here.”

In the light of the powerful torch, several clearly defined footmarks could be seen. They seemed to be those56 of shoes with rubber studs in the soles. One particularly clear one pointed inwards, another, slightly overlapping it, pointed outwards.

“Plain as a pikestaff,” said the inspector. “Any valuables missing?”

Geoffrey Raymond shook his head.

“Not so that we can discover. Mr. Ackroyd never kept anything of particular value in this room.”

“H’m,” said the inspector. “Man found an open window. Climbed in, saw Mr. Ackroyd sitting there—maybe he’d fallen asleep. Man stabbed him from behind, then lost his nerve and made off. But he’s left his tracks pretty clearly. We ought to get hold of him without much difficulty. No suspicious strangers been hanging about anywhere?”

“Oh!” I said suddenly.

“What is it, doctor?”

“I met a man this evening—just as I was turning out of the gate. He asked me the way to Fernly Park.”

“What time would that be?”

“Just nine o’clock. I heard it chime the hour as I was turning out of the gate.”

“Can you describe him?”

I did so to the best of my ability.

The inspector turned to the butler.

“Any one answering that description come to the front door?”

“No, sir. No one has been to the house at all this evening.”

“What about the back?”

57

“I don’t think so, sir, but I’ll make inquiries.”

He moved towards the door, but the inspector held up a large hand.

“No, thanks. I’ll do my own inquiring. But first of all I want to fix the time a little more clearly. When was Mr. Ackroyd last seen alive?”

“Probably by me,” I said, “when I left at—let me see—about ten minutes to nine. He told me that he didn’t wish to be disturbed, and I repeated the order to Parker.”

“Just so, sir,” said Parker respectfully.

“Mr. Ackroyd was certainly alive at half-past nine,” put in Raymond, “for I heard his voice in here talking.”

“Who was he talking to?”

“That I don’t know. Of course, at the time I took it for granted that it was Dr. Sheppard who was with him. I wanted to ask him a question about some papers I was engaged upon, but when I heard the voices I remembered that he had said he wanted to talk to Dr. Sheppard without being disturbed, and I went away again. But now it seems that the doctor had already left?”

I nodded.

“I was at home by a quarter-past nine,” I said. “I didn’t go out again until I received the telephone call.”

“Who could have been with him at half-past nine?” queried the inspector. “It wasn’t you, Mr.—er——”

“Major Blunt,” I said.

“Major Hector Blunt?” asked the inspector, a respectful tone creeping into his voice.

Blunt merely jerked his head affirmatively.

“I think we’ve seen you down here before, sir,” said the58 inspector. “I didn’t recognize you for the moment, but you were staying with Mr. Ackroyd a year ago last May.”

“June,” corrected Blunt.